Rimas Čiurlionis: Painting as the Depths of Meditation

Rimas Čiurlionis –

Painting as the Depths of Meditation

RASA ANDRIUŠYTĖ-ŽUKIENĖ

DR. RASA ANDRIUŠYTĖ-ŽUKIENĖ is an art historian, curator, and modern art critic working at Vytautas Magnus University. Her specialty is twentieth-century Eastern and Middle European art and the cultural heritage of Lithuanian emigrants. She is the author of books on M.K. Čiurlionis and Vytautas Kazimieras Jonynas.

I could compare Rimas Čiurlionis’s paintings to a calm and dignified person. They have a dimension of depth, but not one we are accustomed to, like spatial or perspectives of space and depth; it’s a different dimension, one of spiritual depth. Although they are comparatively large, they do not overwhelm their surroundings; instead they pull you into their right-angled space as if into an eddy. You want to gaze at them for a long time, listening to the nuances of color and the permutations of color and mood, the way we are sometimes silenced watching fading daylight or the flow of rain or a river. Even the geometry and precise forms in Čiurlionis’s paintings don’t appear dimensionless or categorical. In general, the composition of Čiurlionis’s painted works is mysterious and difficult to verbalize. The paintings provide a rare opportunity, not to speak but to be quiet; not to say something to yourself, but to listen to your own inner voice. They prompt meditative reflections, although they are not associated with any philosophical system, nor do they obviously continue any single direction of twentieth- century abstraction. In the act of painting the artist consistently develops his own language of representation, which the observer can approach, but which is actually a personal and subjective artistic expression. They are more hints of emotion than an articulated language of the plastic arts. Understanding the complexity of Čiurlionis’s work and the small chance of understanding it rationally, this article seeks to discuss the peculiarities of the plasticity of Čiurlionis’s painting and clarify the character of this artist’s work.

Čiurlionis began his art studies in Soviet Lithuania at the Stepas Žukas Art College in Kaunas.1 During Soviet times, a freer spirit was discernible at this art school, even if suppressed. In the years 1975–1985, the period of the Soviet Union’s greatest political stagnation, the students at the Art College were famous in the city for their youthful rebelliousness, demonstrative independence, and their formation of unofficial ideological groups. Čiurlionis was part of this student body. Discussions about art and unrestrained creativity that escaped the framework of the school’s official program became a distinctive means of communication in small groups of the like-minded. Their cold and official relations with educators, along with the art students’ constant confrontations, largely contributed to forming the strong and somewhat unforthcoming personalities of the artists. Now they are the well-known middle generation of artists, which includes Čiurlionis.2

An artist’s identity constantly changes, particularly when he is influenced by phenomena associated with globalization, such as migration, the art market, and the dislocation of creative studies. Čiurlionis has worked in Chicago since 1992. The “citizenship” of his art is no longer local. Both the themes and the coloring have changed. The artist’s current field of action is not the homogenous Lithuanian community, but the large and cosmopolitan environment of the United States, which undoubtedly affects the artist with its intellectualism, variety, and strong competition. A good deal of Čiurlionis’s art is already in U.S. and European galleries and private collections. So there is a basis for claiming that his artistic endeavors in an extremely large field are successful and his painting understood and appreciated. “Art is my language, meditation, my conversation myself,” said the artist, for some reason convinced that his artistic language is best understood only by him.3

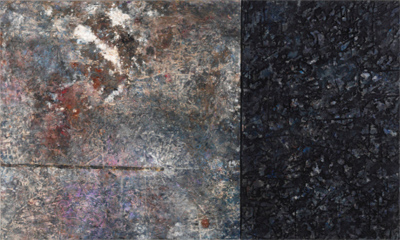

From a generalized and contextual viewpoint, Čiurlionis’s work belongs to the great sphere of the spiritual quest in painting, and relates to tendencies in twentieth-century abstract art. To a question about originality and novelty, a problem in art that has been greatly elevated and invested with meaning in the modern epoch, the artist answers simply: “To me, originality cannot be separated from personal integrity or conviction – a firm belief in what I am doing.” 4 According to him, it is precisely a belief and self-confidence in one’s idea, thoughts, and mastery of technique that is the road to authentic, original, innovative creations the observer will believe in and admire. Things seen in museums and shows provide the artist with visual inspiration, but only if reexamined. For example, the mysterious, curvilinear forms, the sharp and precisely accurate corners of flat surfaces, and the continuous spots of color in the series of paintings “Reflections” and “Palestina” are linked to painting of the postwar U.S. abstractionist phase, Color-Field, Hard-Edge, and minimalism. Čiurlionis admires the work of Lithuanian abstract painter Eugenijus Antanas Cukermanas. They are linked by an understanding of the painting surface as the artist’s field of meditation. They are both characterized by a distinctive approach to the purpose of the painting surface, significantly different from what is usually found in Lithuanian painting. Normally it is the base that is painted, drawn and pasted. Čiurlionis frequently acts otherwise – the painting surface is slowly and patiently formed, covering it with several layers of paint and allowing the colors themselves to move on top of the rough texture, creating indentations, depressions, and hollows. The painting surface in Čiurlionis’s works can be evaluated as an independent asset, as one of this artist’s most original components.

The artistic experience Čiurlionis gathered in Europe and America is used with an aesthetic tact and taste characteristic of the European painting tradition, which the art historian Edward Lucie-Smith named the belle peinture tradition.5 The artist does not deny the importance of impressions experienced earlier in Lithuania and now in the United States. It isn’t the passing emotional impression that matters to him, but the meaning hiding in form, color, and symbols. The artist related that while he was still living in Lithuania, observing village life and exploring Lithuanian folk art, he noticed that signs and symbols frequently have a humble appearance, but their meaning has come from the depths and are extremely meaningful to people. So from Lithuania Čiurlionis brought the awareness that art must be meaningful, not just corresponding to the creator’s state, but meaningful to its viewers as well. “I want meaning,” says the artist, however he does not identify the essential ideas and meaning of his painting. He speaks of painting’s multilayered aspects, the intertwining of thoughts, hints, and allusions. He uses concepts that characterize a peaceful and thoughtful person’s existence, wherever he is in the world.

The singularity of Čiurlionis’s work lies in the sublime peace of the canvas, the meditative depth of the picture, and in the investment of the substance of the painterly surface with significance. The superficial liveliness, the organic feeling, the realization of the optical and physical treatment all delight the viewer and pull him closer to the paintings. The observer can be intrigued by the slowly unfolding understanding that on the painting’s surface he sees not a static illusion of images (and that’s not what needs to be searched out with the eyes), but a slow growth of the artist’s abstracting visual growth, overlapping, mixing, and disappearance. On the one hand, they are subjective; on the other hand, they are processes characteristic of the world in general, and of the nature of artistic creation. Although he masterfully rules the painterly surface, although he knows that he frequently succeeds in suggestively layering his experiences, thoughts and moods, Čiurlionis does not fail to ask himself about the meaning of his creative work. The two questions, “how” and “why” occupy an equally important position in his work.

The note of nostalgia in the iconography of Čiurlionis’s painting is enriched by photographically reproduced images. They are sometimes seemingly accidentally glued on the canvas; sometimes drowned in the mass of paint. People here are merely figures; they are not concrete characters. But to the viewers these images awaken various associations and memories, particularly when paintings with images reproduced on paper make up a cycle (“Ethical Meditations”). Something appears familiar, although it’s difficult to say where those images with people and buildings came from, or what their relationship is with what is rendered in the painting’s plasticity. The viewer is shown “something,” without explaining how it appeared, or why it is one way or another. To the artist Čiurlionis, his own intuitive understanding is paramount: his emotional and intellectual vision – the picture – should appear as it does and cannot appear otherwise.

Translated by E. Novickas

2 This includes Jonas Gasiūnas, Henrikas Čerapas, Elena Balsiukaitė, Rimvydas Jankauskas Kampas, and Vilmantas Marcinkevičius.

3 From a conversation with the author of this article on January 19, 2010, in the author’s personal archives.

4 Ibid.

5 Lucie-Smith, E. Meno kryptys nuo 1945-ųjų. Vilnius: R. Paknio leidykla, 1996, 89.

In 2009 Rimas Čiurlionis’s work was selected by the Art in Embassies Program, US Department of State; his work has been included in gallery exhibits at SOFA – Sculpture Objects & Functional Art in Chicago, IL and he has held solo exhibits at the Lithuanian World Center in Lemont, IL and the Balzekas Museum. The artist has had numerous solo exhibits and commissions in the United States, Lithuania and Germany.

His work has been reviewed in Art Scene Chicago, 2000; The Chicago Art Scene; Lithuanian Artists in North America; and Chicago Tribune.

Čiurlionis received The Lithuanian Society Cultural Award for Art in 2007; a residency award at Lakeside Studio, Lakeside, Michigan and Künstlerhaus Schwalenberg, Schwalenberg, Germany; and second prize at 800 Year Anniversary Art Competition in Lemgo, Germany.

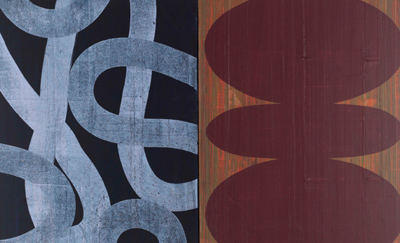

Shapes, oil on canvas, 24” x 40”, 2009.

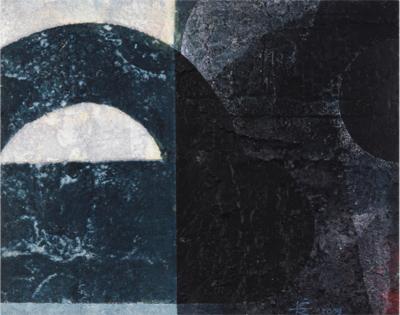

Palestina 5, oil on wood, 13.5” x 16.5”, 2009.

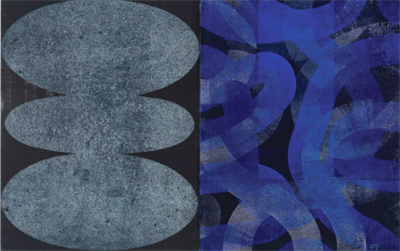

Ethnical Meditations 2, oil on canvas, 36” x 64”, 2009.

Ethnical Meditations 3, oil on canvas, 36” x 60”, 2009.

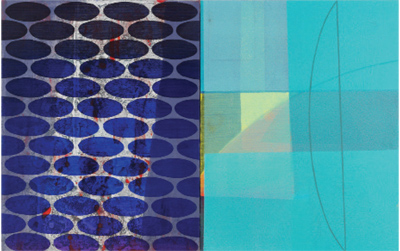

Ethnical Meditations 3, oil on canvas, 36” x 60”, 2009.

Reflection 4, oil on museum board, 25” x 34”, 2009.

Reflection 6, oil on museum board, 25” x 34”, 2009.

Ethnical Meditations 1, oil on canvas, 36” x 60”, 2009.

Palestina 2, 13.5” x 16.5”, oil on wood, 2009.